Since writing the article “The Myth of Left-wing Anti-Semitism” the idea of a companion piece under the title “The Myth of Left-Wing Zionism” has been rumbling around in my head. The obvious inspiration was the incongruence of people considering themselves committed liberals or even solid leftists yet supporting Zionism including the occupation, brutal repression and arguably genocide of Palestinians. But it’s been a difficult challenge to come to grips with as I was raised by parents who were both as left and as Zionist as one can be and it is not hard to understand how they saw no contradiction between the two at the time. The way I’ve come to grips with this is to draw a distinction between “left-wing Zionists” as social justice-seeking people grappling with a very real dilemma for both their community and humanity and the concept of “left-wing Zionism” as an ideological construct consciously designed to incorporate such people into an inherently reactionary settler-colonial project.

A significant portion of the younger generation of Jews raised with progressive values in North America – and elsewhere – are now struggling with the same dilemma: their parents and grandparents are staunch Zionists, yet this seems to totally contradict every other value with regard to social justice they espouse and passed along to their children. They opposed the war in Vietnam, Apartheid in South Africa, incessant US intervention in Latin America, ongoing racism and police brutality at home yet continue to excuse, rationalize and justify the actions of Israel, including of the current far-right Israeli government, in the name of protecting Jews and opposing anti-Semitism.

I know less about my father’s life and family as he died young, of heart disease, when I was ten in 1964. But like my mother he was a member of the Communist Party. I expect that’s how they met – when he came to see family back in Ottawa. Orphaned at three, he was raised by an aunt in New York’s tough Lower East Side where he was in a Jewish street gang before attending City University. A hotbed of political activity; that’s probably where he radicalized and joined the Party.

I thought it might be helpful to begin with my own story of coming to question Zionism rather than an impersonal exposition of the history of the conflict. There is a wealth of reliable sources in this area, some of which listed below under “further references”. While essential, the cold, hard facts of how we came to this current situation can’t address the wrenching emotional conflict taking place within our communities, families and ourselves.

My mother was a leader of the Anti-fascist League in Winnipeg’s north end before moving to Ottawa in 1938 to work as a chemist for the Department of Defense as the country geared up for WWII and there were jobs again, even for women. She had helped organize the large contingent of Jewish and other workers who drove the NAZI’s out of Winnipeg in the battle of Old Market Square in 1934. Then she turned to supporting the volunteers of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (including her then fiancé) who fought the fascists in Spain. When Norman Bethune came through on tour between leaving Spain and heading to China to assist the Red Army, she asked to go with him; but he said they needed nurses not chemists. Otherwise, this might be a quite different story.

I don’t know what led them to quit the Communist Party, it might have been the Hitler-Stalin pact in 1939 or maybe later. I know they were still involved in radical organizing in 1956 when Paul Robeson came to Canada for a brief tour. This is a picture of him in our dining room raising a glass to Mitchell and Denise. I don’t expect he had the time or inclination to drop in on random white folks so it is reasonable to assume they were central organizers of the meetings and concerts that were arranged for him. I must have been there but at just two years old, too young to remember meeting this world-famous actor, musical icon and social justice champion.

I can’t say at what point they became ardent Zionists. During the 1930’s it is reasonable to expect they followed the Party line but by the end of WWII they were fully involved – and they never did anything by halves. Our family name is not obviously Jewish and my father, at six feet tall and two hundred solid pounds did not fit the common stereotype of the mild little Jew. This made him the perfect front man for a military surplus business secretly financed by a very wealthy Jewish-Canadian family. A fortune derived in part from supplying prohibition America with good Canadian whiskey.

Britain and British Commonwealth counties prohibited the sale of any of their huge store of now surplus military equipment to the Haganah which was engaged, along with the Irgun and Stern Gang, in a terrorist campaign against the British in Palestine. But it apparently wasn’t a challenge to fake final user documents and whatever other paperwork was required to help equip the nascent Zionist army. Not for people with plenty of experience – and no qualms about – working around laws and borders. As a kid about my only toys were a tank driver’s helmet and a pilot’s cap and life vest left over from that venture.

Later they spearheaded the building of the first synagogue in Don Mills, the new suburb of Toronto where we lived in the fifties and my mother led the local Hadassah chapter. And we got the full after-hours Hebrew school routine, Jewish summer camp and synagogue seats, at least for the High Holidays. Of course, they remained unabashed atheists but it’s easy to understand after the trauma of the Holocaust why maintaining and rebuilding Jewish culture and community was an imperative for them – as well as supporting Israel.

I expect their commitment to Zionism wasn’t just a reaction to the Holocaust. As informed political activists they would have been well aware of the collusion of Western elites and governments with Hitler in the lead up to the war and the obstacles put in the way of Jews escaping from the NAZIS after 1933, as well as the difficulty of bringing over those few who survived after the war ended. Even for Jews who did not personally feel compelled to move there, Israel must have seemed like they finally had a lifeboat, a place of last refuge, if things ever went bad here as they had in Europe. Again, they had direct experience with this; a cousin on my mother’s side would stop by from time to time when his sales rounds brought him to the area and mom mentioned they had worked to get him to Canada from a displaced persons’ camp after the war.

One could say they were just carrying on a family tradition. My mother’s great grandfather was apparently a famous figure in the southern Ukraine. Like many Jewish boys he was conscripted into the Tsar’s army at the age of twelve. Somehow, he survived twenty-five years of imperial wars and returned to his shtetl as a decorated sergeant with special permission to travel freely and open an inn/roadhouse. He was known as the “giant of Schwartz Shtima” according to family stories I heard as a kid and a little self-published book an uncle wrote after he retired. He was six feet four with heft to match. Reportedly, pogromists kept their distance from his village while he was around. And he lived through the entire 19th century, finally passing at the remarkable age of 103.

His son, my great grandfather, was not such an imposing and courageous figure and the story is he died when a pogrom occurred in a neighbouring village he was visiting. With no visible signs of trauma, the family assumed he died of fright. More charitably, perhaps a stress-induced heart attack. But his son Baril (my great uncle) took after his grandfather in both physique and courage. He was a member of a Jewish self-defence group organized by the socialist Jewish Bund and had to be smuggled out of the country with the Tsarist secret police hot on his trail; finally winding up in Winnipeg’s North End, like so many others fleeing eastern Europe in the first years of the 20th century. That’s why the rest of the family (including his sister, my maternal grandmother) wound up there when they were left widowed and fatherless.

I take after my grandfather who was just a wiry 5’9” but apparently packed a punch. When a newly hired big Ukrainian balked at taking direction from a Jewish lead hand on the factory floor (in not too complimentary terms) Jack laid him out with a single uppercut to the jaw and his authority was unquestioned after that. I mention all this to be clear my family was no stranger to anti-Semitism in its most virulent forms and this knowledge was foundational to my upbringing. As I know it was for all of us. But perhaps differently from many, the intrinsic message was that in my family at least, no matter where we were – the Ukraine, Winnipeg or New York City – we didn’t take it lying down.

After the passing of more than fifty years it’s hard to say what exactly led me to first have doubts then serious disagreement with Zionism. I recall in 1967 when the six-day war broke out I made a bet with a Christian-Arab friend from Lebanon (his family owned the local neighbourhood corner store) then felt guilty about collecting the dime. Partly it seemed unfair to take money for such a sure thing but also perhaps a hint of doubt about whether I had backed the right side. I recall when I heard my seventeen-year-old brother who was an ardent member of USY (United Synagogue Youth) tell my mother he wished he was a year old older so he could join the IDF I thought it was a ridiculous idea but kept silent. So, I must have already started to question the Zionist narrative we’d been raised on. (To his credit, he radicalized afterwards and joined the anti-Zionist left.)

Of course, this was many decades before there were computers, the internet and social media where one can now easily access historical documentation and alternative narratives. I can’t claim to have had any special insight or powers of prediction so I can’t say for certain where these doubts came from. It might have been the jarring dissonance between the values I learned from my parents and from the Talmud in Hebrew School and what I was discovering about Zionist ideology and practice. It was impossible to ignore the unabashed and ubiquitous racism expressed towards Arabs, especially in the context of the six-day war. They were all “stupid, cowardly, barely civilized” so easily beaten by the Israeli army. Supposedly, whole companies would surrender at the sight of one IDF soldier.

It was all so similar to the derogatory stereotypes of Indigenous, Black and other oppressed and colonized people that were so dominant in mainstream discourse and that my parents taught us were so wrong – when it came to all these things we were on the other side. So why were Palestinians an exception?

And then there was the blatant ridiculousness of the slogan: “a land without people for a people without land”. One didn’t have to be a historian, or even a grown-up, to know that the Palestinians hadn’t appeared out of thin air after the first Zionist settlements appeared. It was so obviously copied from the doctrine of discovery and terra nullis propagated by the Catholic popes to justify settle-colonialism in the Western Hemisphere and the genocide of the Indigenous inhabitants from the Arctic Ocean to Tierra del Fuego. And I’d been sent to the principal’s office for declaring in grade 8 Canadian history class that the problem with burning Christian missionaries was that the Indigenous people hadn’t done all of them. So clearly even then I didn’t see Western Christian colonialism as an example Jews should be following.

But this racist conceptualizing of Palestine as “empty of people” at the end of the 19th century was fundamental to the invention of left-wing Zionism as an ideological movement. They had to deny the reality that Palestine had a well-established population living and thriving throughout the territory, from the lush farming country of the Galilee to the southern desert, from the rich bustling fishing grounds and ports of the Mediterranean to the Jordan River; not to forget the orange, olive, fig and nut orchards of the central regions in addition to hilly grazing areas where herds of sheep and goats were maintained. There were hundreds of villages, towns and a number of important cities with rich family, cultural, religious and political traditions; largely Sunni Muslim but that fully integrated other significant communities including Christians, Druze and Jews.

It was only as an adult that I had the opportunity to learn more about this reality but the founding Zionists were well aware of it. But how to justify and proselytize their ambition to take over this land – and the violent ethnic cleansing it would inevitably entail? This in a time when the European empires were increasingly seen as the rapacious and oppressive colonial regimes they were. Including, and perhaps especially, among the socialist leaning Jewish working class of Eastern Europe.

Peoples of Central and Eastern Europe ruled by the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, and those of the Caucuses under Ottoman rule, were beginning to stir with nationalist aspirations. Zionism was inspired by and modeled on these movements. But these involved people seeking independence and self-determination within geographic areas where they had long composed the majority. Zionism had the dilemma of being an unwieldy – one might say illogical – combination of two conflicting historical trends: forging an ethno-national project but doing so with the patronage of one of the dominant empires on a land already fully occupied by an Indigenous people.

Much is made of the role of the Balfour Declaration in laying the foundation for the creation of Israel in 1948. Less well known is that the early Zionist leaders shopped the idea around all the major capitals of Europe, including Istanbul and St. Petersburg before hitching their wagon to the British Empire when it became clear it would replace the Ottomans as the dominant power in the Middle East. But they were clever enough to know that selling Zionism as the last hurrah of European colonialism was not going to fly with the bulk of their prospective supporters who were deeply enmeshed in, or at least sympathetic to, the budding anti-imperial movements of central and eastern Europe at the close of the 19th century and opening of the 20th. So, the Palestinian people had to be first erased from Zionist mythology, before being erased from memory, then erased from the land – or buried beneath it as in Gaza at this moment.

After my Bar Mitzvah I took one more year of weekly seminars with our rabbi. In the course of our theological discussions, he admitted to being agnostic. I was surprised at the time but looking back it’s not that odd. I expect very few Jews – even the most observant – actually believe in a personal, anthropomorphic deity who talks (or talked) to people from burning bushes or pillars of fire – or carved commandments on slabs of rock. But if that’s the case, I thought, what does that mean with regard to a supposed biblical claim to a land we hadn’t lived in for two millenniums. Of course, every Passover for those two thousand years Jews intoned the words “next year in Jerusalem” but no one was actually planning to join a caravan or get on a boat. Certainly not the hundreds of thousands of Jews who lived all around the Mediterranean and the Middle East for whom it wouldn’t have been a big deal. A longer journey for those in Eastern Europe but not impossible as the crusaders demonstrated. And there was a small but vibrant Jewish community centered in Jerusalem throughout the 1400 years of Muslim rule.

That all changed with the advent of political Zionism in the last decade of the 19th century when European anti-Semitism reached new heights in breadth and virulence. But it was clear to me, that whatever the justification for creating a Jewish national state on the territory of Palestine, it couldn’t be rationalized by a biblical claim none of its proponents actually believed. Herzl, Weisman, Ben Gurion and their colleagues were all secular Jews. Maybe it was my own prejudice but I figured they knew it was just a good story to tell the gullible goyim (gentiles) whose support was needed and who were actually dumb enough to believe in the literalness of the Old Testament. Recently reading more on the lobbying around the issuance of the Balfour Declaration confirmed what I suspected those decades ago. Sir Arthur James Balfour and other major figures in and around the British government were devout Christian Zionists and the Zionist leaders played them like a fiddle, just as they do today with far-right US evangelicals.

Another likely factor in my growing skepticism was that we were not just anti-racist but anti-imperialist. Every night I watched the news that was more and more filled with images of the American war on Vietnam and the growing protest movement in the US and around the world. By the time I was fifteen I was marching against Canadian complicity with the war. It may not be the most solid foundation for taking a position on the issue of Palestine but as it became clear that Israel was closely aligned with the US and its foreign policies it just seemed logical to be on the other side. With hindsight and the benefit of much more information about the history and current situation I am happy to see that using the rough guideline of judging someone or something by their friends and alliances – while not foolproof – pointed me in the right direction.

The icing on the cake, you might say, came when I was 18. After being forced out of her profession as a chemist – like tens of thousands of other women fired to make room for the men returning from war – my mother returned to it after my father died. After all, she had four children to support. Now in her fifties, and after being away from the lab for more than two decades, she quickly became a pioneering expert in the new field of spectroscopy that was supplanting test tubes and Bunsen burners for chemical and forensic analysis. There was a scientific conference in Jerusalem and in deference to the eleventh commandment – “never pay retail” – Denise arranged to be a delegate so her employer, the federal government, would pay her airfare and hotel.

So, the summer I finished high school in 1972 my mom took me to Israel. Her explicit hope was that seeing the reality of Israel would alter my views. Of course, it had the exact opposite effect! The building of settlements in the occupied territories – in violation of international law – had already begun though was still in early stages. This clearly proved to anyone with their eyes open that the rhetoric about wanting peaceful coexistence, if only the Palestinians would agree, was a lie. As is undeniable now, and I presciently surmised at the time, this trajectory would make the so-called two-state solution completely untenable. We now know that the ethnic cleansing of the entirety of historic Palestine was always the objective of Zionism.

But even more viscerally repulsive was the blatant and pervasive racism of Israeli society, not just toward Palestinians but non-Ashkenazi Jews. More jarring than just casual disdain, there was the explicit derogatory language used when referring to anyone who had come to Israel with darker complexions from the long-established Jewish communities throughout the Middle East and Africa. It didn’t just affect me; I could see my mother tense up and grit her teeth as she resisted the urge to get into what would have been non-stop confrontations with almost everyone around her.

She told me it was the lower living standard compared to Canada that made her turn down the offer of a teaching position at the Hebrew University but I strongly suspect it was a broken heart at comprehending the reality of Israel compared to the illusions she once held. Perhaps that was combined with guilt for the role she and my father had played – small as it was – in bringing it into being. We never really spoke about the trip again and if Israel came up in the news my normally voluble mom just got strangely quiet and looked away.

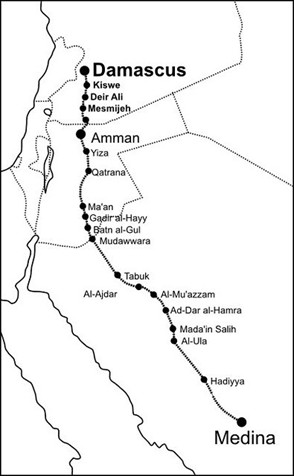

I recently discovered that Zionist territorial ambitions had even gone farther than seemed apparent in 1967 – or 1972. The Zionist Organization’s initial proposal to the League of Nations discussing the British Mandate asked that the Jewish national home be established within the following borders:

“… In the north, the northern and southern banks of the Litany River, as far north as latitude 33° 45′. Thence in a south-easterly direction to a point just south of the Damascus territory and close and west of the Hedjaz Railway.

“In the east, a line close to and west of the Hedjaz Railway. (see map)

“In the south, a line from a point in the neighbourhood of Akaba to El Arish.

“In the west, the Mediterranean Sea.

We also now know from David Ben Gurion’s own words that acceptance of the 1947 partition plan was understood as another of their strategic manoeuvres to maintain international support, not a repudiation of the ultimate goal of taking all of Palestine. It was seen as a necessary stepping stone in a process that might take a generation or two. But they could be patient. Events leading up to 1967 provided the opportunity and they took it. Anyone who thinks Israel will voluntarily relinquish the occupied territories is dreaming. The possibility of the so-called “two-state” solution has been foreclosed by the settlements and all the other infrastructure of Israeli Apartheid.

Another whole article could be written about the history and myths of left-wing or “labour” Zionism: the kibbutz’s, the Histadrut (Jewish trade union movement), all the other cooperative, charitable and political institutions that were built up from the first years following the First World War – including the Labour Party itself which dominated Israeli politics into the 1970’s. In many ways it was an attractive, even compelling vision for progressive Jews who believed in social democratic or even more radical alternatives to capitalism. Inherent and even often explicit in this vision was the claim that peaceful coexistence with the Arabs of the area, and the region, was possible and desirable.

But there was a fatal flaw, an insoluble contradiction in this claim. No people in the world, or ever in history, would accept their homes and land being usurped by newcomers claiming some mythological primacy over the territory. By insisting on Jewish exclusivity first in employment, then in all the other social and political components of the Yishuv (Jewish community under the British Mandate) and finally in the Israeli state itself after 1948, the Zionist movement, including the dominant labour variety, ensured the antagonism and rejectionism of the Palestinians.

The Israeli propaganda line is that peace was always possible if only the Arabs would accept it, would reconcile themselves to first the 45% of Palestine proposed in the UN partition plan, or the 22% not ethnically cleansed during the Nakba or the 2% not under direct Israeli occupation today. But this is to propose reconciling the irreconcilable, to demand acceptance of the unacceptable. The fact is, at each conjuncture when Palestinian leadership was open to coming to terms – albeit reluctantly – with the undeniable existence and overwhelming military power of Israel, the Zionists simply moved the goal posts: less land, less real sovereignty, less adherence to international laws and norms. Combined with assassinations, provocations and other manoeuvres such as building up the Muslim brotherhood and Hamas against Fateh and the PLO to make good faith negotiation impossible. As vehemently – sometimes violently – divided as Israeli politics may appear at times, on these essential strategic perspectives it is impossible to find daylight between the left and right sides of Zionism when it comes to actual actions on the ground.

In many ways the views of the so-called Revisionists like Vladimir Jabotinsky were more refreshingly honest. In 1923 he declared: “To think that the Arabs will voluntarily consent to the realization of Zionism in return for the cultural and economic benefits we can bestow on them is infantile. This childish fantasy of our “Arabo-philes” comes from some kind of contempt for the Arab people, of some kind of unfounded view of this race as a rabble ready to be bribed in order to sell out their homeland for a railroad network.”

This perspective has been borne out as the true reflection of the inevitable logic of Zionism. No Indigenous people has ever willingly accepted displacement and dispersion by a foreign settler-colonial movement although there is guarantee that resistance to sometimes overwhelming military force will be successful. Labour Zionists denounced such views as far-right, even fascist but that did not stop their military wings from working together in the anti-British terror campaign of the 1940’s or the ethnic cleansing campaign launched in late 1947 against the Palestinians – and still ongoing.

The real objection of the labour Zionist leadership to such language was that it was terrible public relations; such honesty about the objectives and implications of Zionism would alienate large swathes of Jewish opinion in Western Europe and North America as well as the governments on whose diplomatic, financial and military support the Zionists knew were crucial to their success. And in a sense they were right. When good people, Jews and non-Jews alike, realize what Zionism as a movement and Israel as a violent and oppressive settler-colonial state are really about they whole-heartedly reject it. As I did as an adolescent, as I’m confident my parents would have had they lived to see the horrors of the occupation and hopefully as you will.

I’ll end with one more little anecdote. During the winter break when I was seventeen, I took a stroll while visiting my older sister in Montreal. A twenty-ish Hasid ran out from a little synagogue to the snowbank encased sidewalk and asked me if I was Jewish. It seems one of their regulars had taken ill and they were one short for a minyan for evening prayer. It seemed an odd question and request but I knew how important it was for the observant so or course I agreed. It must have been an odd sight, nine Hasidim in traditional garb and one hippy kid with a kippah balanced precariously on his bushy-hair, davening together. The incongruity certainly brought a smile to the face of the venerable rebbe. And I daresay I would do the same today though I expect my Hebrew is a little rusty after so many years.

Just to say, no matter what some might claim about those of us who are not observant and especially those of us who support Palestinian liberation, a Jew is a Jew is a Jew. And no one, especially not Zionists and their apologists who have betrayed the commitment to justice, righteousness and peaceful human co-existence that Judaism should stand for, can take that away from us.